Rob's Flash Messages

Rob's Stories

How The Omniverse Works

I have always been deeply fascinated by the phenomena of our universe. Solar and star systems, the Big Bang, black holes, dark energy and matter and especially the theories surrounding quantum fields and relativity intrigued me endlessly.

I have always been deeply fascinated by the phenomena of our universe. Solar and star systems, the Big Bang, black holes, dark energy and matter and especially the theories surrounding quantum fields and relativity intrigued me endlessly.

This fascination brought forth questions that constantly occupied my mind, such as: "What existed before the universe and what comes after?" "Why can’t we properly relate gravity to the other three fundamental forces?" "Why do we know so little about dark matter?" "Will we discover more elementary particles after the Higgs?" "What is spacetime and what happens if it ceases to exist?" — and many more.

These questions are no different from those that have puzzled renowned scientists for decades. Yet, after reading something by Penrose and with a nod to the inspiring TV-series "How the Universe Works", I felt that even his perspective did not present a fully holistic view. Something was still missing, leaving all the above questions unanswered.

I became ambitious. I wanted solutions and extensions of existing theories and although speculative and divergent from the mainstream consensus, still rooted in physics.

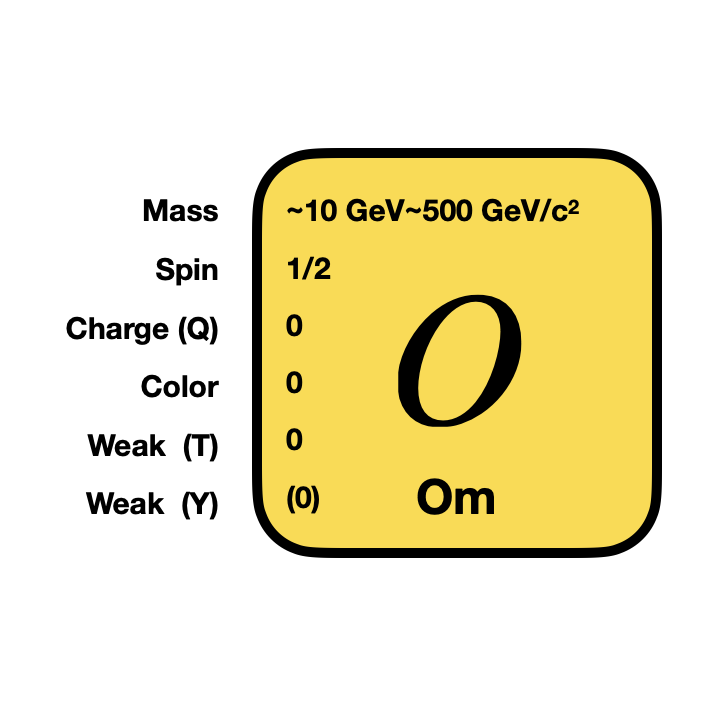

To explain the concept of the Omniverse, I propose the existence of a new fundamental and (fermionic) quantum field: the O-field. Unlike the quantum fields we know from modern physics, which exist only within the framework of spacetime, the O-field is more fundamental and omniversal. It exists everywhere — even in regions where spacetime itself does not. Key to its role is the generation of energy through differences in entropy within the field, a process that gives rise to what we perceive as dark energy.

Want to read the full story? Get it here: How The Omniverse Works as PDF or as EPUB here.

Enjoy!

Update: The first version calls the proposed O-particle an O-Quark. While this is an appealing term to most readers, it is misleading to physicists. By definition, a quark has color charge. The O-particle does not. So in the latest version of this booklet, the name of the particle has been changed to O-Fermion. A 1-minute scan and replace, but still it was a mistake. My bad.

2050 and beyond - part 3

A Changing World Population

Significant shifts are already evident. Not too long ago, children in the Netherlands were seen as economic assets, pension guarantees, or even religious absolutions. In other parts of the world, this is still the case. The average number of children per family in the Netherlands has dropped from 4.5 in 1900 to just 1.6 today. This decline is the main driver of population aging. Japan, with an even lower birth rate of 1.3 children per family, shows where this can lead. If trends continue, Japan’s population—already shaped by much lower immigration than Europe—will drop from 125 million today to just over 90 million by 2050. By then, there will be one working-age Japanese person for every retiree or child. Projections suggest the population could shrink to 64 million by 2100 or shortly thereafter—half of today’s level.

It’s plausible that the rest of the world will follow this trend, with similar consequences. However, the varying speeds of demographic change across regions will cause significant shifts—almost resembling mass migrations. By 2060, an estimated 35% of the Dutch population will be of non-Dutch origin, up from 25% today. This shift is inevitable and doesn’t need to be feared—it’s simply a result of global development. A diverse society offers many advantages, provided we invest in its success rather than hinder its progress.

Disruption on a Societal Scale

The developments described above will profoundly disrupt society. Current demographic models, political debates, and TV discussions already struggle to provide meaningful insights. They often base their projections on incorrect short-term population figures, focusing on just one generation. Whether this disruption ultimately benefits or harms humanity depends on perspective. The human species as we know it will cease to exist—biologically and technologically, we are rapidly evolving—and so will projections based on today’s humanity.

Politicians often speak of “preparing the Earth for future generations,” but these are hollow phrases. Medical and technological advancements will transform humanity within a single generation. The generations that follow will be unrecognizable by today’s standards and may need to be understood in cycles spanning centuries rather than 15 to 25 years. The real question is which segments of humanity—on both national and global scales—will adapt first, and whether the rest will be pulled along or left behind.

Rethinking Work and Income

Work and income, as we know them, are economic constructs that will need to be reimagined. They may even cease to exist altogether. Discussions and experiments surrounding a universal basic income frequently resurface, reflecting this potential shift. Once we complete the energy transition and learn to heat and power our homes almost for free using solar, wind, and water energy supplemented by clean nuclear power, enormous financial resources will be freed up—resources that are currently almost literally being burned. These funds could either be saved or reinvested in innovation, especially to protect our own economic interests. A fully automated circular economy may eventually leave room only for services related to care and entertainment.

Of course, policymakers argue that such changes can’t happen all at once. They’re too costly and too mentally challenging for people to process quickly. While this is true, a faster pace wouldn’t hurt. The Dutch and global political landscapes currently resemble a store selling car wheels—each unique, yet all round with a rim and tire. But when fitted to a car, they don’t align properly and don’t provide a smooth ride.

A Vision for the Future

It is shocking that the Netherlands has no population target for its future. We set ambitious CO2 reduction goals for 2050, yet no objectives for the primary driver of emissions: the number of people living here. As a result, the government chases fluctuating statistics and extrapolations year after year. This leads to inconsistent housing policies—one year we’ve “built enough,” and the next we suddenly need 1.5 million more homes. As a society, we avoid confronting the true vision of the future, as it’s seen as too grim, too uncertain, and too unpopular to discuss. Scientists are left to speculate, and everyone else then forms an opinion about their findings.

Ultimately, the question isn’t whether we should prioritize or hinder any specific age or population group. It’s about defining how humanity wishes to exist on this planet, what privileges we grant ourselves, and which consequences we’re willing to accept—for ourselves and others, both locally and globally, in the present and the future. This is the crux of the debates on television and at the ballot box. These discussions will determine how historians judge the behavior of Generations X, Y (Millennials), and Z (Zoomers), who currently dominate the political and corporate spheres. Together, they will decide whether there is a valuable world left after 2050.

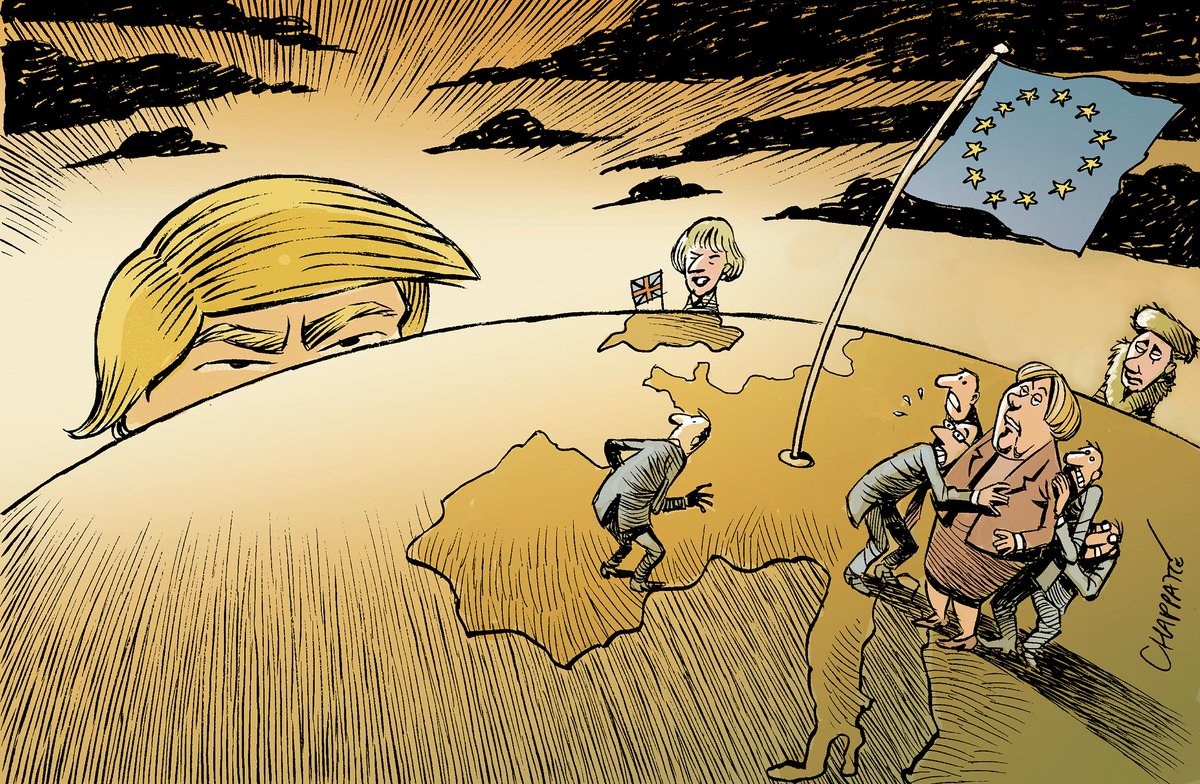

Unfortunately, media portray a less-than-hopeful image. Indifferent, anti-scientific, and self-centered populists incite hyper-nationalistic behavior in their electorates. On the other side, scientists and entrepreneurs stay narrowly focused on their fields, unwilling to see or address the larger impending changes. In the middle, we find Dutch celebrities—experts in their fields of art, science, literature, or business—offering opinions on everything else. Entertaining, perhaps, but rarely grounded in substance.

Generation Alpha: A New Beginning?

The generational alphabet has run out of letters. We’ve started over with Generation Alpha. Let’s hope they initiate a new kind of Genesis by 2050. Perhaps we should skip a few letters and call them Generation G—Generation Genesis. After all, they will likely live for over a century.

Sources:

(1) https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2020/51/prognose-bevolking-blijft-komende-50-jaar-groeien

(2) https://www.nibud.nl/consumenten/wat-kost-uw-kind/

(3) https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telomeer

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Singularity_Is_Near

(5) https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/achtergrond/2018/51/prognose-bevolking-naar-migratieachtergrond

(6) https://www.ewmagazine.nl/nederland/achtergrond/2020/05/geen-tijd-om-kinderen-te-krijgen-over-corona-en-de-bevolkingsgroei-757038/

(7) https://www.statnews.com/2020/02/21/human-reproductive-cloning-curious-incident-of-the-dog-in-the-night-time/

(8) https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/ranglijst/ranglijst-doodsoorzaken-op-basis-van-sterfte

(9) https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-bevolking/bevolkingsgroei/geboren-kinderen

(10) https://www.uchiyama.nl/ngjapankortdemogr.htm

2050 and beyond - part 2

Public debates and popular TV discussions with various "experts" and demographic models routinely falter for three main reasons: biological/medical, technical, and social.

Medical Advancements

First, let’s consider the development of medical science. We are on the brink of a major transformation. Diseases that currently require curative treatments may soon be preventable through genetic therapies. I, for instance, suffer from a genetic disorder (DFNA9), which leads to complete deafness, total loss of balance, and severe tinnitus at a relatively young age. Recently, a drug has been developed that can largely prevent the damage caused by my DNA’s mis-coded proteins. The next step would ensure that these proteins are no longer mis-coded at all. Such treatments are already being applied to diseases caused by a single genetic defect, such as cystic fibrosis, hemophilia, and DFNA9. Within one generation, more complex genetic combinations will also be addressable.

Genetic therapy isn’t just for preventing diseases. It also enables changes to an individual’s traits. In doing so, we take evolution into our own hands. This opens up ethical concerns reminiscent of The Boys from Brazil, but that doesn’t change the fact that there is room for improvement in humanity. Children dream of being as skilled in sports as their idols on TV—a dream that often requires more “talent.” That talent may soon be genetically engineered: taller, shorter, stronger, with greater endurance, faster recovery—whatever the goal demands. Intelligence could be enhanced, and perhaps we could even address our natural propensity for violence.

What about cloning—currently an almost taboo subject? It seems unlikely that humans will be transported en masse to Mars and beyond. It would be far cheaper to create humans on-site. And why not reuse a proven, well-functioning “model”? Improvements could even be made “on-the-fly.” Sustaining 80-kg humans for months or years during space travel is laughably dangerous and expensive. After a few pioneering missions, it would be more practical to use frozen embryos—or perhaps just a DNA blueprint and a printer. Developing these embryos could be done naturally, but artificial methods may be required, especially if pregnancy in low or zero gravity proves unviable.

Cloning could also become a reality on Earth. While it’s currently prohibited, the fact remains that it’s possible. And if it’s possible, it’s likely to happen at some point, whether officially or in secret. From a demographic perspective, the question is whether humanity is ready to embrace cloning on a large scale and in what numbers. Many reasons exist why potential parents might want this option. However, I believe that cloning will not have a significant demographic impact on Earth this century due to insurmountable ethical objections. On Mars, however, it’s a different story.

More immediately significant is the likelihood that aging itself will be treated as a “disease” within the next 25 years. While multiple factors contribute to aging, one key issue is the damage to telomeres—the ends of DNA strands—caused by cell division. Treating this damage is challenging, as telomeres also play a role in 85% of cancers, so manipulating the repair process could backfire. But assuming scientists overcome these hurdles, these cancers may soon be preventable or curable. This is critical, as cancer is currently the leading cause of death in the Netherlands, claiming over 30,000 lives annually.

If aging can indeed be significantly delayed or prevented, those born today may never die of old age—at least not within the first 100-200 years, barring accidents. The demographic and economic consequences of this would be staggering. Without radical measures, we’d face explosive population growth, the collapse of pension systems, and extreme shortages of energy and food, among other challenges.

Technological Advancements: The Singularity

The second, often overlooked development is technological: the emergence of the singularity—an Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) far superior to humans. Opinions differ on the timeline, but its arrival is inevitable. The big question is when. Ray Kurzweil, a scientist at the intersection of cognition and technology, predicted in 2005 that this point would be reached around 2045. While initially met with skepticism, his timeline seems to be on track, if not ahead. Developments like Tesla’s autonomous cars and ChatGPT are only the beginning.

Whether humanity must eventually acknowledge its intellectual superior in an artificial brain is less important than the impact AGI will have. Technologically, it will drive innovation; economically, it will transform the labor market; socially, it will redefine what it means to be human. For instance, if drivers of cars, buses, trucks, trains, boats, planes, and rockets are soon to relinquish control, the next target for AGI will likely be professions governed by strict rules or procedural structures. Accountants, administrators, notaries, lawyers, programmers, teachers, and knowledge-based consultants could all be replaced.

While high-pressure environments requiring creativity or human interaction may still demand human input, the idea that work will remain exclusively human is unrealistic. In fact, a collaboration between humans and AGI in knowledge-rich, unstructured environments could prove to be the ultimate competitive advantage.

Shifting Self-Perception and Demographics

Finally, there’s the matter of our self-perception—not just as individuals but as humanity as a whole. Do we really need 17 to 22 million people in the Netherlands? Or 7 to 10 billion globally? Perhaps 10 million in the Netherlands and 5 billion worldwide—or even fewer—would suffice. Public debates rarely address humanity’s reproductive drive, treating it as a given and a matter of personal freedom. But can we sustain this?

The world is becoming overcrowded, and we’re also destroying it—especially with these population levels. Resistance is growing. The issue isn’t whether the planet “fits” us but whether it’s pleasant and desirable. Green voting trends are pushing for large-scale CO2 and nitrogen reductions. We pressure countries like Brazil to stop destroying rainforests and ecosystems. People are turning against large livestock industries and adopting vegetarian lifestyles. Resistance to excessive immigration is rising, and it won’t be long before harder voices question even autonomous population growth and the assumed right to reproduce.

Even child benefits may face scrutiny. Should individuals who consciously choose to remain childless because of the ecological footprint of offspring still contribute to incentives for reproduction? While society cannot afford for individuals to make such choices independently, it will undoubtedly influence voting behavior and, consequently, representation in government.

2050 and beyond - part 1

The Case

The debates surrounding the COVID-19 measures in 2021, and continuing to this day, have increasingly focused on what society can still endure, with particular attention given to the younger generation. There has been dramatic talk of a “lost COVID generation.” On TV, open discussions were held about whether it would be better to isolate the elderly so that younger people could reclaim their freedoms and get their lives back on track. Some even argued that older people—bluntly labeled as “dead wood”—should reflect on whether their lives have already offered enough. Meanwhile, young people, whose lives have yet to begin, should be prioritized, with the elderly stepping aside.

The argument is that the younger generation forms the economic engine: they work, they pay the taxes that support the rest of society. That’s partially true, at least regarding income tax. The employment rate for those aged 25 to 55 in the Netherlands is about 85%. For those over 55, it drops by 15%, and after that, it declines rapidly to zero.

But this perspective overlooks several things. While income tax contributions do decrease as people age—since they work less or not at all and often fall into lower tax brackets—older adults still pay VAT, excise duties, property taxes, water board levies, energy taxes, motor vehicle taxes, and even the much-despised wealth tax (Box 3) on savings, which were already taxed earlier. Of course, there are a few ultra-wealthy individuals for whom money seems to fall from the sky, but the resentment they inspire usually outweighs any financial gain from taxing this group more heavily.

Consider also that 4.5 million people over 60 already make up 25% of the Dutch population. This share is projected to rise significantly over the next 50 years to approximately one-third, assuming stable parameters. According to Statistics Netherlands (CBS), this ratio, along with the total population size (estimated to range between 17.2 and 22 million), could vary considerably depending on factors like migration trends and preferences for having two children. A “dip” in autonomous population growth due to the COVID-19 crisis is already visible, as some people seem to be postponing their desire for children.

This makes it unlikely that the "economic engine" of 25-to-55-year-olds can sustain itself. After all, they also need to finance their own reproduction. The average Dutch two-parent household with two children spends 25% of its disposable income on raising them.

On top of this comes the climate crisis—if it is indeed universally regarded as a crisis. While global warming is an undeniable fact, some politicians question its causes (humans or overpopulation) or prioritize economic growth and prosperity over immediate climate action. Moreover, the effects of climate change are not always and everywhere negative. This ambiguity is eagerly exploited by climate deniers. However, CO2 emissions are just one consequence of humanity’s insatiable hunger for more—a hunger matched by a relentlessly growing global population. Other examples include the depletion of natural resources, massive pollution, the plastic soup in rivers, seas, and oceans, the extreme destruction of flora and fauna, the pressure on habitable space, and ongoing conflicts—all stark reminders of humanity's impact.

So...

We must start seriously thinking about building and maintaining a sustainable society, both locally and globally, where all generations—each with their own distinct characteristics—are given an equitable and meaningful place in society. Every generation has had, or will have, its strengths and weaknesses. Achieving this requires a clear understanding of the current size of these groups and how they will develop over the next 100 years, as people born today could easily live that long (barring disasters, wars, accidents, or inadequate healthcare, whether self-inflicted or otherwise).

The recent COVID-19 crisis may have sparked this critical thinking. It is, after all, deeply unpopular to condemn an entire generation—or multiple generations—simultaneously. As a result, spokespeople often circle around each other in these debates. They talk about long-term effects but mean short-term ones. This frequent misunderstanding hardens positions and even revives political ideologies we thought were left behind 75 years ago.

Page 2 of 6